Spilt my hot chocolate all over the table on the ferry · Seen tonnes of posters for the recent election · Hugged my oma and papa for the first time in six years · Visited her in her new flat · Bought a bami kroket… thing from a vending machine · Eaten brunch with the entire family · Got locked out of a fare gate · Accidentally sat in first class · Relaxed in the quiet carriage · Marvelled at the futuristic toilets on the train · Contemplated faith at the Begijnhof · Hugged a tree in a bookshop · Ambled past a makeshift Ukrainian cultural centre · Walked through residential Amsterdam neighbourhoods in the rain · Got high · Laughed at the animals at the zoo · Had a staring contest with an otter · Read a sign explaining their elephant had PTSD · Savoured the sweet taste of appeltaart · Been freaked out by mandrils (they just looked like deformed children dragging their arms along the ground to me) · Sweat half my weight in water out in the butterfly garden · Watched microbial scientists at work · Wondered why they had binturong poop but no binturongs · Been confronted with a dead baby giraffe

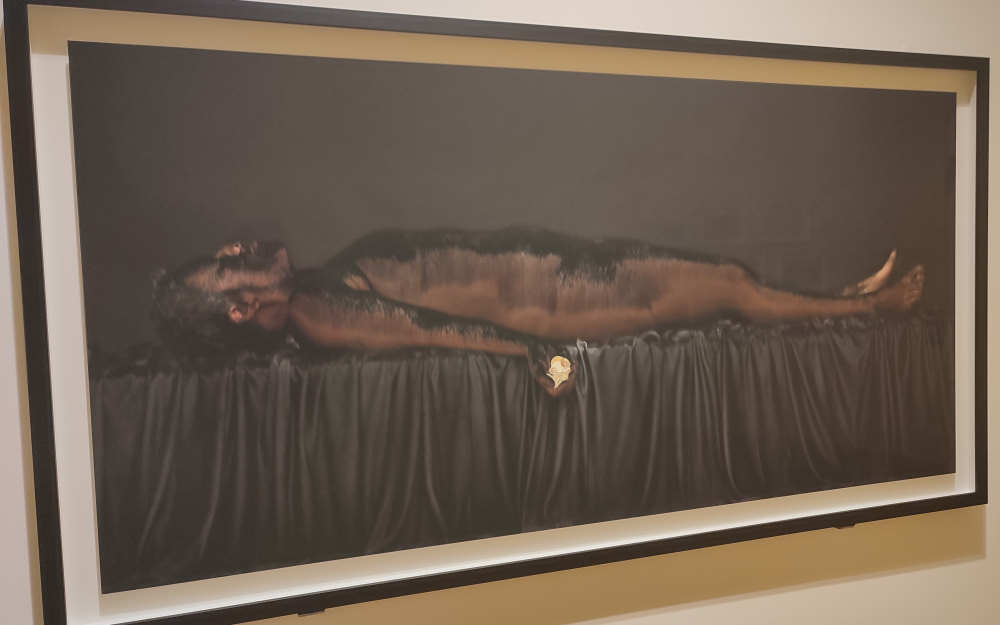

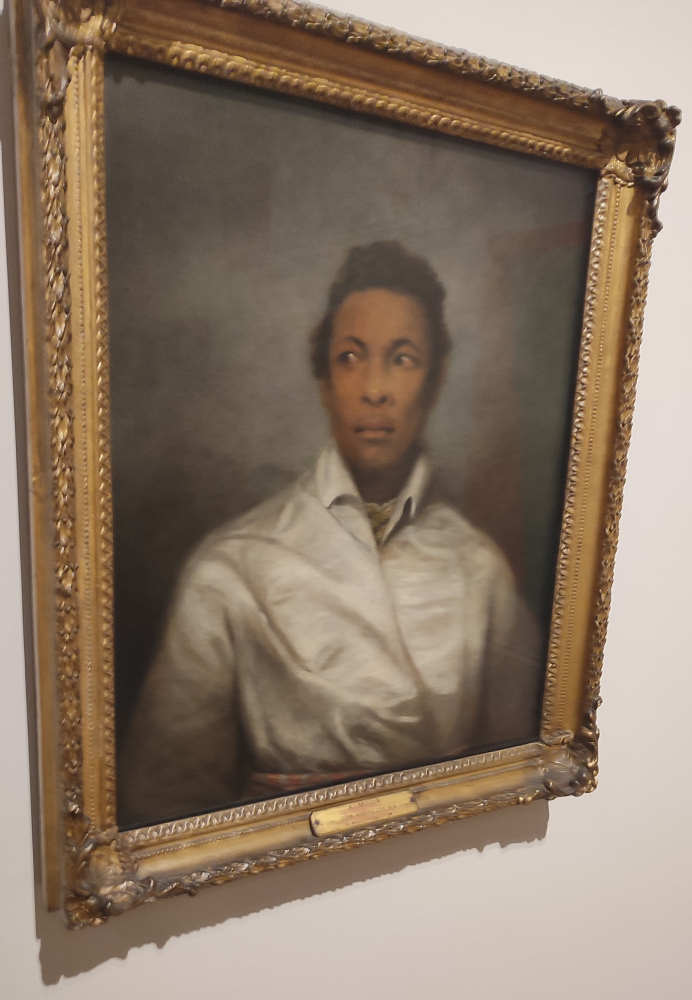

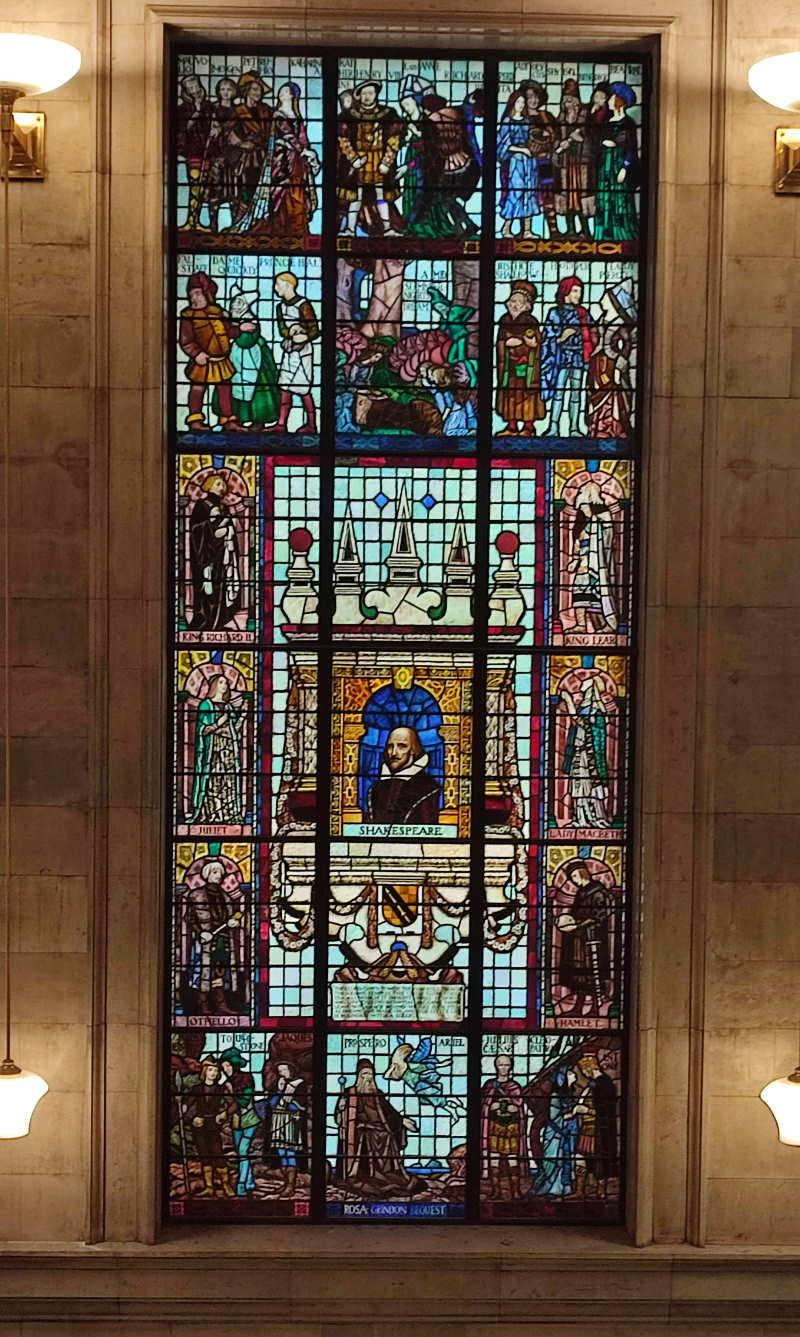

Realised that that’s not a clock, that’s a giant wind rose · Found out that six years later, they’re still restoring The Night Watch · Discovered new favourite paintings · Admired the gumption of defeating the British in naval battle and hanging their coat of arms up in the Rijksmuseum · Seen possibly the first condom ever displayed in a prestigious art gallery · Wondered just how Jac van Looij made those blues so blue · Felt smugly superior to everyone crowding around the three Van Goghs · Learned that that painting that looks like a photo was, indeed, based on a photo · Confronted the Netherlands’ colonial legacy via diorama · Remembered that Louis Napoleon was King of the Netherlands for a bit · Ogled at some surviving Renaissance smut · Marvelled at the syncretism of the Græco-Buddhists · Had my route back home interrupted by the Sinterklaas parade · Scoffed at the price of McDonald’s · Wished i’d just taken the plane, whilst trying to get to sleep · Wished i had stayed longer · Made plans to go back.